Let me lead you through this…

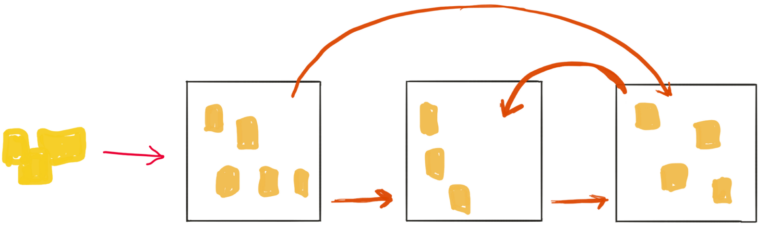

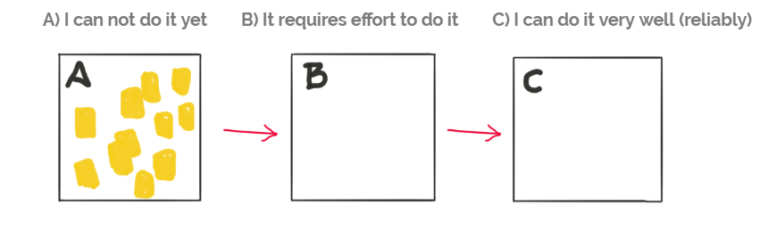

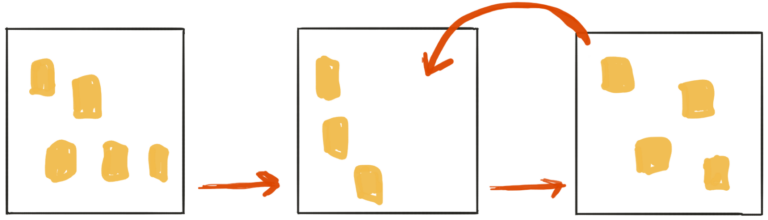

In the beginning, each skill we try to obtain is in box A, it means we can’t do it yet.

Do we progress by choosing a few things we can’t do well, then we learn how to do it, we practice a lot and we’ll be able to do it extraordinarily? Is this really how we develop excellent skills?

There are some problems with this approach:

This logic suggests that we obtain skills or capabilities starting from A to B and B to C sequentially. But there are also some skills that we can learn automatically from A to C, skipping the intermediate stage.

For example, if we lead a team, we presumably have some experience in people management. If we want to learn a new skill, our existing capabilities also have an impact on acquiring it in a much shorter time.

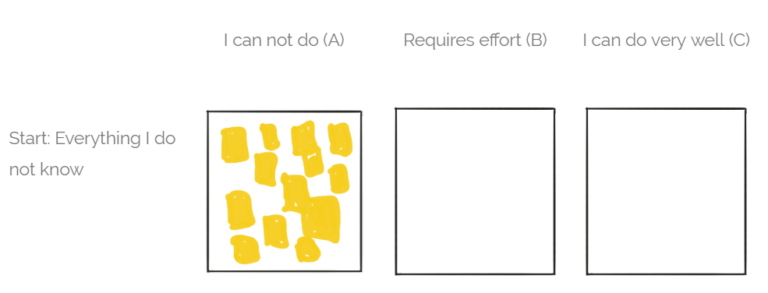

When we take a closer look on experts, we can notice that A is never empty, they always try to acquire new skills or they want to improve something that they already know.

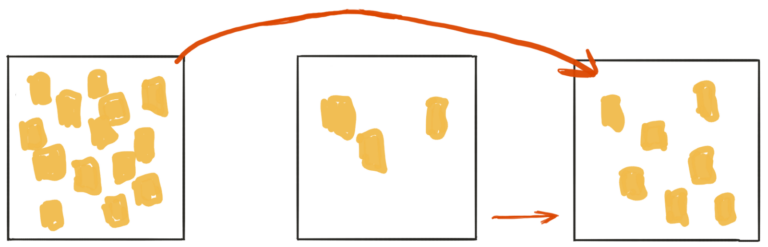

The third problem is that gurus not only improve their capabilities from B to C, but sometimes they return from C to B. The question is fair, why would we want to “rebuild” something we already do well?

On one hand, we use skills in everyday life which are not always developed consciously. It can be something we do well, even though we have not practiced it too much. For example, you often can see people skiing good enough, at an intermediate level, so to speak. In many cases this level is not consciously achieved, they got better and better just by doing it for long. Almost automatically, so deeply captured that we do not even notice it. However, if we want to ski at a professional level, we have to go back and decouple an automatism we evolved during practicing and choose a (only one at once) small technique that we consciously learn to do better or differently.

On the other hand, it may sound strange at first, but we can not even maintain our level of knowledge if we only use our existing knowledge. What we do on a very good level becomes routine, we may no longer think about it but we automatically pull it out of our toolbox. Maybe you caught yourself to think of a situation why you exactly acted the way you did. Most likely, you could have used a skill automatically and not consciously, let’s say from your routine toolbox. I usually say in this cases that “at the moment it looked like a good idea.” :))) It seems that not only those things wear out that we know but don’t use, but also those that we use every day without consciousness. It’s simply because we do not recognize the relationship between the situation and the skill used.

How do experts develop themselves?

You probably have already encountered a phenomenon that two people practiced the same amount but eventually did not reach the same. One possible explanation is that one of them was more talented than the other. Anoter may be that the more successful person was more effective in practicing. He did not do harder or longer, but more efficiently.

If we practice more and harder, we potentially will be worse overall, as if we practice less.

Let’s imagine we learned to play piano at some level. Then we have taken a lot of time to practice. We play piano at a higher level now, but at a certain point we feel stucked and we do not really get better. Despite many practices, we are as mediocre as we were. Why will we be potentially worse? If there are more things we do at a mediocre (or acceptable) level and spend a significant amount of time with polishing them, we can experience the above phenomenon in more things, so we get stuck with more things. Practically, there will be fewer things in box C, the ones we are really good at. We can say in business terms that the Return of Investment is poor.

Last year, a potential client approached us with a large but poorely designed leadership development project. We had our doubts, but it still seemed a good excercise for our younger colleagues at first sight. However, we finally politely refused the opportunity with a conclusion: “Why should our junior experts supposed to practice on a wrong setup when they can do it on a good one?”

The biggest problem with most mediocre people is that they keep too many things in box B. I would suggest this logic instead: